4310 Church History in North America

Links: 6. History,

Credit: Class Notes from Dr. Theodore G. Van Raalte's Class on Church history

This course covers church history in North America from the 16th c. to the present. Colonization, the Awakenings, the rise of Evangelicalism, and more recent Canadian developments receive attention. The history of the Canadian Reformed Churches (and a few other Reformed churches) is studied in this context.

Files

Church History In America Timeline

Lectures

1. Church History in the Americas: Intro

Orientation

- Our own immediate geographical and cultural context

- Revival? What brought about, "No Creed but Christ!" Mainline to sideline & vice versa?

- Whence all the sects and cults? Slavery? The “crusades”?

- Where was the Lord preserving his church?

- Narrow and broad uses of “church”

- Church as the body of Christ

- Patterns of growth and decline

- When we study history for what it is, we can be improved, critiqued, enlightened.

- In the world but not of the world. Sometimes those in history are more in the world than of it.

- Watch for 'revivals' that were politically motivated, their context effected them.

Christopher Columbus

- 1492, sailed the ocean blue. He was the First Christian in the Americas.

- But, do the Vikings count? Some Vikings were Christians. Newfoundland settlements.

- Colonialism

- Cultural mandate

- Edenic command

- The idea of 'going out' and governing the land is a biblical land.

- Babel curse

- We are supposed to spread out.

- Edenic command

- Great commission

- Jesus taught to make disciples to spread the Gospel to all nations. Highest authority.

- Seek what is good

- It is evitable that cultures will come into contact with one another. Sharing the Gospel is one way that this happens. Ultimately the desire must be for the good of another culture/people group.

- Movement of peoples is normal

- Take the medonightes for example, they fled to Ukraine, Russia, and North America; all to find freedom to worship.

- Cultural mandate

- Columbus’s Millennialism

- Believed that the Earth was a globe. A smaller globe than we might think. He was very religious.

- Christopher = Bearer of Christ

- Believed his voyage was Fulfilment of prophecy, "God showed me where to go."

- When they found land: "Glory to God in the Highest"

- Living in the end times . . . gold needed for great crusade. These eschatological views, may have led to his poor treatment of the natives.

- Believed that the Earth was a globe. A smaller globe than we might think. He was very religious.

- John Cabot

- Italian with English money and authority, going to the “new founde land,” 1497. Henry the 7th, Church building there c. 1500?

- Possible first ever church building:

- Mission: To investigate heathen lands not otherwise known to Christians.

- Italian with English money and authority, going to the “new founde land,” 1497. Henry the 7th, Church building there c. 1500?

The Story of the Guanabara Confession of Faith (1558)

Context: France and Religious Freedom

- By 1563, there were 2,150 Reformed churches and preaching points in France.

- 1593 King reverted to Catholicism to appease the people in Paris

- Financer: Gaspard de Coligny, a prominent Huguenot nobleman and Admiral, played a key role in supporting Reformed efforts.

- Links up with Villegagnon

The Venture to Guanabara Bay

- Captain Nicolas Villegagnon

- Secured Coligny’s backing for the expedition.

- Established a settlement on Villegagnon Island in Guanabara Bay, named Fort Coligny.

- Sent a letter to Calvin asking for Reformed Leadership

- Reformed Leadership

- Two pastors, Pierre Richier and Guillaume Chartier, accompanied the expedition. Also some laymen:

- Shoemaker Jean de Léry later documented the experience, producing an anthropological text. Extensive: Language, dance, experiences, etc.

- Two pastors, Pierre Richier and Guillaume Chartier, accompanied the expedition. Also some laymen:

- Lord’s Supper

- Celebrated on March 21, 1557, marking a significant moment of faith in the colony.

- Marriages

- Two couples were married on April 3, 1557, under Reformed practices.

Conflict and Division

- Villegagnon’s Interference

- Initially supportive, Villegagnon began to oppose the Reformed community.

- Held some Roman Catholic superstitions that he demanded must be implemented. (Oil + Salvia in Baptism). Pastors reject. Pastor Guillaume Chartier was sent back to France as tensions grew.

- Villegagnon calls Calvin a heretic, Genevan citizens face prosecution. Some escape to live with the natives.

- Initially supportive, Villegagnon began to oppose the Reformed community.

- Reformed mission to the natives

- Language barrier, barbarism, but beautiful jungles and beautiful songs

- Psalm 104 while on a hike through nature with natives. They want to know what the Song means.

- No word for God in their language so he used the word of thunder.

- Another time the natives asked who the people were 'speaking too' when they were praying before a meal

- Jean de Léry, shoemaker, preaches for two hours with an interpreter.

- They pray and share that they will not human flesh. But, later that night they reverted back to their ways.

- A ship then arrives to take back some of the people. They board the Jacques, to return to Europe, but it leaks only a few hours after the voyage.

- Four tradesmen return: Jean du Bourdel, Matthieu Verneuil, Pierre Bourdon, and André de la Fon

- Villegagnon believed them spies, orders them/ tests them on their beliefs.

- Advised to not answer, but to escape. But the men replied as Christians that they must stay and give an account of their faith, which led to this "Guanabara Confession of Faith"

- All these men are under the age of 22.

![[Guanabara Confession 1558.pdf]]

- 1 Peter 3:15 authorizes us to give a reason for the hope that we have. Thus, the Guanabara Confession!

- Natives would ask ew settlers to sing to see if they were good or bad.

- Praise God for the creedal imperative that arises in our hearts. Let us be faithful, gladly confessing Jesus Christ as Lord, looking forward to living with him in peace and joy for life eternal

2. First Christians in Americas

Sarah Irving-Stonebraker, Priests of History: Stewarding the Past in an Ahistoric Age (2024)

- Author came to faith in 2007, during doctoral studies, after attending a series of lectures by the virulently atheistic ethicist, Peter Singer.

- Notices an ahistorical age, since about 2010.

- Inventing oneself is the height of existence; there are no traditions, histories, inheritances, transcendence (xxi).

- Christians struggle to make sense of history, to inhabit story as God’s people.

- History is reduced to simplistic ideology.

- Authenticity, self-expression are key.

- We create ourselves. Rip down statues.

- “No forgiveness in secular hell,” argues Jeff Mallinson.

- New purpose for museums.

- History majors fallen by half.

The Classical Idea of a Divinely Ordered Cosmos is Lost

- Thus, interest in the purpose and telos of life is lost (8).

- Today we need to know how it works rather than what it means and its purpose (11).

- In liberal Christianity, “individual religious experience” is the locus of truth rather than the Bible,

and thus historical traditions and confessions are deemphasized in favor of highly personal feelings and emotion (12-13).

Five Major Characteristics of the Ahistoric Age (6, 17, 20, 25–38)

- We believe the past is merely a source of shame and oppression from which we must free ourselves.

- We no longer think of ourselves as part of historical communities.

- We are increasingly ignorant of history.

- We do not believe history has a narrative or purpose.

- We are unable to reason well and disagree peaceably about the ethical complexities of the past—that is, the coexistence of good and evil in the same historical figure or episode.

Spanish Colonialism

- Population decline: 25 million native inhabitants in the area of Mexico around 1500. By 1600, only 1.2 million.

- 75–90% of native populations either died of disease or were killed off.

- Guerra a fuego y a sangre—“a war by fire and blood” to remove the threat of natives.

Bartolomé de las Casas (1484–1566)

- “The entire human race is one … all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.”

- Death of Hatuey?

- Killing for sport.

- Spanish colonists treated the native population like dogs, perhaps even lower than that. They killed them for sport, and though nothing for the murder they were committing. A glimpse into our depths into depravity.

Las Casas defends natives.

- Spanish colonists treated the native population like dogs, perhaps even lower than that. They killed them for sport, and though nothing for the murder they were committing. A glimpse into our depths into depravity.

- Las Casas became a fierce opponent of the encomiendas.

- Some laws made to protect slaves.

- Forced labor in mines was most resented.

- “For it is better to live by the sweat of one’s own brow than by another’s blood.”

Lessons for Us Today

- Be gospel-centered.

- Bring the whole counsel of God.

- Love all people.

- Oppose injustice.

Jean Ribault and the Huguenots

- Sponsored by Gaspard de Coligny, 1562 (like Villegagnon to Guanabara in 1557).

- Charlesfort & Fort Caroline (N & S Carolinas’ names).

- Early psalmody in Florida.

- 1562 contact with the Timucuan natives. Psalmody and Genevan Psalter. Natives use Psalm 128, 130 to greet new settlers to see if they were French or not. Loved the music.

Fort Caroline (1562–1565)

- Ships destroyed in a hurricane. Spanish move on to the Fort. Succeed in battle. Ask for an unconditional surrender, the French agree.

- Men killed by Spaniard Menendez as martyrs, Sept 1565, because they were “Lutherans.”

- They were Reformed, subscribed to the Gallican Confessions (Belgic is based on this Confession).

- Fort Matanzas, site of slaughter of Huguenot men, Sept 1565.

First Settlements in America

- Fort Caroline, 1562 – [South Carolina]. Huguenots.

- Charlesfort, 1562 – [Florida]. Huguenots.

- St. Augustine, 1565 – [Florida]. Roman Catholics.

- Jamestown, 1607 – [Virginia]. Puritans. (Named after KJV Bible)

- Plymouth, 1620 – [Massachusetts]. Puritans.

- Savannah, 1733 – [Georgia]. Freedom of worship.

Jamestown, 1607

“We greatly commending, and graciously accepting of, their desires for the furtherance of so noble a work,

which may, by the Providence of Almighty God, hereafter tend to the glory of His divine Majesty,

in propagating of Christian religion to such people as yet live in darkness and miserable ignorance

of the true knowledge and worship of God, and may in time bring the infidels and savages,

living in those parts, to human civility and to a settled and quiet government;

Do by these our letters patents, graciously accept of, and agree to, their humble and well-intended desires.”

– Charter from King James I, April 10, 1606

Christian Instruction in the Colonies

“And we do specially ordain, charge, and require, the said president and councils,

and the ministers of the said several colonies respectively, within their several limits and precincts,

that they with all diligence, care, and respect, do provide,

that the true word, and service of God and Christian faith be preached, planted, and used,

not only within each of the said several colonies and plantations,

but also as much as they may amongst the savage people which do or shall adjoin unto them,

or border upon them, according to the doctrine, rights, and religion now professed and established within our realm of England.”

– Charter from King James I, December 10, 1606, Article 3

Early Church Life in Jamestown

*“When first we went to Virginia I well remember we did hang an awning (which is an old sail)

to three or four trees, to shadow us from the sun; our walls were rails of wood;

our seats unhewn trees till we cut planks; our pulpit a bar of wood nailed to two neighboring trees.

In foul weather we shifted into an old rotten tent; for we had few better, and this came by adventure for new...

- This was our church till we built a homely thing like a barn, set upon cratchets, covered with rafts of sedge and earth; so was the walls. The best of our houses of like curiosity, but the most part far much worse workmanship, that neither could well defend wind nor rain. Yet we had daily Common Prayer, morning and evening; every Sunday two sermons; and every three months the holy Communion, till our minister died; but our Prayers daily with an Homily on Sundays, we continued two or three years after, till more preachers came...”*

– Captain John Smith, 1631

Pocahontas, d. 1617

- Powhatan (father)

- Captured in 1613, held for ransom.

- Converted to Christianity, decided to stay with the English, later took the name Rebecca.

- April 1614 married to John Rolfe, brought to England, learned English. Used to gather support for Jamestown

“She lives civilly and lovingly with him, and I trust will increase in goodness, as knowledge of God increaseth in her. She will go to England with me; and, were it but the gaining of this one soul,

I will think my time, toil, and present stay well spent.”

Pocahontas was kindly received in London; by the care of her husband and friends she was, by that time,

taught to speak English intelligibly; her manners received the softening influence of English refinement,

and her mind was enlightened by the truths of religion.

– Charles Campbell, History of Virginia (1860), 115

Mission Mandated by Civil Authorities, 1619

- In 1619, the First General Assembly convening in Virginia, in order to lay a sure foundation for turning the Indian tribes to Christianity, commanded the authorities of each town, city, borough, and plantation in the Colony to secure by peaceful means a certain number of Indian children with a view of bringing them up in a religious and civil course of life.

- The most promising of these native youth were to be grounded in the rudiments of English learning in order to fit them to enter the college which it was proposed to set up, and when they had been graduated from this institution, they were expected to go out as missionaries among their Indian kindred.

Source: Colonial Records of Virginia, Assembly Minutes, 1619, vol. 1, 5–6. - Anglican- Cranmer's Prayer book

Mayflower - England -> Leiden (Separatists) -> New World

- Rev. John Robinson, debated against Remonstrant opponents; leaned Reformed

- Puritan, Congregational

- Plymouth Colony

Week 3: Jonathan Edwards

Jonathan Edwards Lecture FULL

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) was born into a ministerial family in a Congregational Church in Connecticut in 1703. His mother, too, was the daughter of a minister, Rev. Solomon Stoddard of Northampton, Massachusetts. Biographers say that her remarkable mental abilities were well known. Edwards was educated at Yale (New Haven, Connecticut), starting in 1716, at age 13.

Some theologians and historians will tell you that Edwards is still the greatest theologian of the Americas. He is known for his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” He is known for writing on the Religious Affections. He might be known by a few people for getting kicked out of his church because he wanted church membership and participation in the Lord’s Supper to be restricted to members who had publicly professed faith in Christ. I hope to explain this event. Let’s continue with a brief biography.

By age 19, in 1722, Edwards served a Presbyterian church in New York State. He provided eight months of regular preaching as a non-ordained supply pastor (began Aug 1722). His Master’s degree at Yale was complete at age 19, in Sept. 1723.

Edwards questioned himself and his conversion 1722-1723 at times because he didn’t follow the formula of conversion that his grandfather had set forth, for he lacked terror when he was convicted of his sins. He then concluded that actually there is no rigid, set pattern that the Holy Spirit necessarily follows in each conversion. Holiness of life became very important to him.

In his personal narrative, Edwards recounts a time in his childhood when he awakened to spiritual things, only to fall away again. As a teen he struggled fiercely against the sovereignty of God. How could it be just for God to elect some but damn others? As Edwards struggled with this, he also prayed, and God’s Spirit took away his doubts (c. 1721). His heart was opened. He writes that “God's absolute sovereignty, and justice, with respect to salvation and damnation, is what my mind seems to rest assured of, as much as of anything that I see with my eyes; at least it is so at times.” By God’s grace, he came to delight in this teaching. He wrote, “The doctrine of God's sovereignty has very often appeared, an exceedingly pleasant, bright, and sweet doctrine to me: and absolute sovereignty is what I love to ascribe to God.” He added that a new sense of joy in God himself followed this. He began to sing to himself repeatedly, “Now to the King eternal, immortal, invisible, the only wise God, be honour and glory forever and ever, Amen" (1 Tim 1:17). Edwards describes his inner thoughts and religious affections. He had a new apprehension of Christ, of the way of salvation. “I had an inward, sweet sense of these things, that at times came into my heart; and my soul was led away in pleasant views and contemplations of them. And my mind was greatly engaged, to spend my time in reading and meditating on Christ; and the beauty and excellency of his person, and the lovely way of salvation, by free grace in him.”

Edwards loved God’s creation, and his account also highlights time spent on a path, in a forest, among the trees, the birds, the clouds, the sunshine, the water, and the grass. Thunder and lightning were sweet to him. Edwards is very personal and experiential about this: “And I used to spend abundance of my time, in walking alone in the woods, and solitary places, for meditation, soliloquy and prayer, and converse with God.”

He further recounts: “My longings after God and holiness, were much increased. Pure, humble, holy, and heavenly Christianity appeared exceeding amiable to me. I felt in me a burning desire to be in everything a complete Christian; and conformed to the blessed image of Christ: and that I might live in all things, according to the pure, sweet, and blessed rules of the gospel.” He writes much about his desire to be holy.

You may find the details, the passion, the emotion of his account unusual. Do we speak this way? Do we think this way? Consider this beautiful passage, “Holiness, as I then wrote down some of my contemplations on it, appeared to me to be of a sweet, pleasant, charming, serene, calm nature. It seemed to me, it brought an inexpressible purity, brightness, peacefulness, and ravishment to the soul: and that it made the soul like a field or garden of God, with all manner of pleasant flowers; that is all pleasant, delightful and undisturbed; enjoying a sweet calm, and the gently vivifying beams of the sun.”

We think of holiness as fighting sin, of dedicating ourselves entirely to God. Edwards wrote,

There was no part of creature-holiness, that I then, and at other times, had so great a sense of the loveliness of, as humility, brokenness of heart and poverty of spirit: and there was nothing that I had such a spirit to long for. My heart as it were panted after this, to lie low before God, and in the dust; that I might be nothing, and that God might be all; that I might become as a little child.

He also recounted periods of deep joy and satisfaction in Christ, in the Spirit, and in the Word. He was deeply joyful, rejoicing to share with his readers his experience of these things. At the same time his sense of his own wickedness grew; his sin appeared to him to be “infinite upon infinite.” He noticed the “bottomless, infinite depths of wickedness, pride, hypocrisy and deceit left in my heart.”

Let us finish with a positive description in his Personal Narrative: “Another Saturday night, January 1738-39, had such a sense, how sweet and blessed a thing it was, to walk in the way of duty, to do that which was right and meet to be done, and agreeable to the holy mind of God; that it caused me to break forth into a kind of a loud weeping, which held me some time; so that I was forced to shut myself up, and fasten the doors. I could not but as it were cry out, "How happy are they which do that which is right in the sight of God! They are blessed indeed, they are the happy ones!”

Two of Edwards key, leading ideas were holiness and beauty. Those are such positive things, and unless we devote ourselves to them, we will find ourselves lacking in good vocabulary about them. Edwards can help us find the right words.

But why did Edwards describe these experiences of conversion and regeneration so closely? Let’s keep that question in mind as we continue.

Edwards expressed his commitments in 70 formal resolutions, written in 1722 and 1723. He introduces them with these words, “Being sensible that I am unable to do anything without God’s help, I do humbly entreat him by his grace to enable me to keep these Resolutions, so far as they are agreeable to his will, for Christ’s sake. Remember to read over these Resolutions once a week.” Let’s hear three of them:

- Resolved, that I will do whatsoever I think to be most to God's glory, and my own good, profit and pleasure, in the whole of my duration, without any consideration of the time . . . whatever difficulties I meet with, how many and how great soever.

- Resolved, to endeavor to obtain for myself as much happiness, in the other world, as I possibly can, with all the power; might, vigor, and vehemence, yea violence, I am capable of . . .

- Resolved, never to do anything but duty; and then according to Eph. 6:6-8 do it willingly and cheerfully as unto the Lord, and not to man; “knowing that whatever good thing any man doth, the same shall he receive of the Lord.”

Edwards served as a tutor at Yale from 1724-1726. In 1727 he was ordained in Northampton, to assist his maternal grandfather, Solomon Stoddard. He was to be “scholar pastor,” 13 hours per day in the study. In the same year he also married Sarah Pierpoint, 17-year-old daughter of the Congregationalist minister, Rev. James Pierpont (founder of Yale College in 1701; died 1714). Contemporaries wrote that they were blessed with a lovely, godly, complementarian marriage. They received eleven children. Numerous offspring of theirs, through the generations, served in academic, judicial, and political leadership.

Let’s get back to our question: Why did Edwards describe these experiences of conversion and regeneration so closely? You might know that some of our forefathers in the faith were not favourable to this kind of preaching or even such personal stories. They said that these were too emotional, too concerned with conversion, too man-centred. Let’s think about this. We may differ from each other in our opinions on this, but let me explain the circumstances so that we can weigh our opinions carefully.

We need to speak about precincts and covenants in the midst of Congregationalist church life in the American colonies. We are in the time that led up to the American Declaration of Independence, which came in 1776. Edwards did not witness it. He died in 1758 from taking an experimental smallpox vaccine. Likely his dose was contaminated, but we don’t know. He was always interested in and well-educated in science, and understood the idea of the vaccine.

But back to the precincts and covenants. Edwards lived in “New England.” This was the name for six states or colonies of England: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. He was born in Connecticut, schooled there, and then served a church in Northampton, Massachusetts for about 25 years (including the 1.5 years of preaching after he had been dismissed). Other colonies or provinces of England had the Church of England (Anglican) as their official, established church (NY, NH, ME, VA, NC, SC, GA). But the New England colonies were all or mostly Congregational. Certainly Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire were Congregational. This meant that the taxes that were collected were also used to set up “Meeting Houses” and to pay the ministers of the churches.

The first Congregational church was established in Plymouth in 1620. Congregationalists were Reformed in doctrine, holding to the Westminster Standards. However, they did not agree to parts of the Westminster Standards that confessed the need, qualifications, and authority of elders. The Cambridge Platform laid out their position on church polity.

Mark Noll speaks of the Cambridge Platform. This was a very important document created in 1648 by the Puritans of Massachusetts.

The first key point of the Cambridge Platform is that they regard the form of the church to be “the visible covenant, agreement, or consent, whereby [the covenanting persons] give up themselves to the Lord, to the observing of the ordinances of Christ together in the same society, which is usually called the church covenant: For we see not otherwise how members can have church power one over another mutually.” Thus the form of the church is not established by elders, or by faith, profession of faith, cohabitation, or baptism, but only by this church covenant. Keep this in mind when we talk about the “half-way covenant” in connection with Jonathan Edwards.

The second key point is their view of authority or power in the church. Section V.2 states, “Ordinary church power, is either the power of office, that is, such as is proper to the eldership, or power of privilege, such as belongs unto the brotherhood. The latter, is in the brethren formally, and immediately from Christ, that is, so that it may be acted or exercised immediately by themselves; the form is not in them formally or immediately.” This means:

- Christ has directly endowed ordinary church members with authority

- The elders and deacons have authority through the means of these members

As a result, a company of professed believers who “confederate” or covenant together with a church covenant, will be a church of Christ even if they lack office bearers. This point is directly contrary to the Presbyterian and Reformed view. The brotherhood of the church, in the Cambridge Platform, has the power to: a) choose their own elders and deacons; and b) admit their own members and excommunicate their own members. Elders (incl. ministers) and deacons who don’t rule well are subject to the power of recall by the church members, who can remove them from office (X.6,7).

One can sense that the Platform struggles to explain how the elders and deacons have authority over the church members and yet are also subject to censure by the church members. This polity had a parallel and perhaps origins in a movement in France that the Reformed churches there had opposed.

These Congregationalist Puritans set up a kind of theocratic society. When they arrived in a new place, they set up a “Meeting House.” This was the name of the building in which Edwards’ preached. This generic term, “Meeting House,” was used for both the civil and the ecclesiastical context. On Sunday, the church met in this building, but on other days the precinct’s civil authorities met there. The same people were involved in both spheres and were expected to be. The colonies were akin to theocracies. All the members of society were to be members of the church. In Massachusetts one had to be a church member in order to vote civilly. This structure functioned in Connecticut until well after the American Revolution, for it ended in 1818. Massachusetts maintained Congregational churches for seven more years, until 1825.

What’s likely to become a problem in a theocratic society? Well, if your membership in the church is kind of taken for granted because you belong to the body politic, and if there are political benefits to belonging to the church, such as the right to vote, church membership will no longer be truly voluntary. People will join the church in name, but not in heart. Nominalism results.

Indeed, one of the problems that arose in New England in the second and third generation of settlers was a lack of elders in the churches. Already in 1679 the Massachusetts General Court appointed a “Reforming Synod.” This assembly sounded the warning that elders needed to function in the churches, or their church government would descend into either a prelatic (prelacy, a bishop) or popular mode. The diminished number of elders coincided, as one might expect, with a diminished number of converted members. Fewer people professed their faith. They were thus considered “unspiritual.” At this time, the conversion narrative, like Edward’s Personal Narrative, was an important feature of the Congregational churches. Having such a story gave evidence of the Holy Spirit’s converting work and underlined the importance of true faith for church membership. Religious experiences were important. Since such accounts were no longer common, the ministers needed a way to keep their people in the church, allow them to have their children baptized, and perhaps allow them to go to the Lord’s Supper. Church was central to society. The half-way covenant was devised already in the 1650s to allow the baptism of children whose parents had not had a conversion experience and had not professed their faith. Such parents could not go to the Lord’s table and they could not vote, but the baptism of their children would be permitted.

In Northampton in the early 1700s, Edwards’s grandfather Stoddard had gone further. He had begun to allow members who had not professed their faith to participate in the Lord’s Supper. He reasoned that the Lord’s Supper was a “converting ordinance.” His unspiritual people, who thought themselves to be unconverted, could take and eat in the hopes that this would help them reach conversion. As long as they didn’t lead a “scandalous life,” they could come. I assume that they still could not vote, but they did at least have a “¾ covenant,” shall we say.

Jonathan Edwards followed this practice in Northampton for all of his ministry. But in 1749 he came to a different position, and within the year this cost him his ministry in Northampton. We could jump ahead to 1749 but then Edwards’s position might seem like a surprise to us. Whereas if we were to follow him through his preaching, through the Great Awakening, and through his long struggle over the religious affections, his actions in 1749-1750 will make more sense to us.

We’ve already read three of Edwards’s 70 resolutions. We’ve also listened in on his Personal Narrative, his own account of his conversion and his calling. We also have some sense that he lived in the midst of a society that sought to have all of life lived before the face of God. This man was passionate, determined, and deeply moved to live for God’s glory.

To get at the question of the Great Awakening and the religious affections, let’s listen in on him preaching his famous sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.”

It was July 8, 1741. His text was Deut 32:35, “Their foot shall slide in due time.” These are covenant words of warning that Moses pronounced against the Israelites at the end of their 40 years of wandering. In the opening paragraph of his sermon, Edwards was clearly drawing a line from the text to his congregation. He preached that God was threatening vengeance “on the wicked, unbelieving Israelites” who were, “God’s visible People, and lived under Means of Grace; and that, notwithstanding all God’s wonderful Works that he had wrought towards that People, yet remained, as is expressed, ver. 28. void of Counsel, having no Understanding in them; and that, under all the Cultivations of Heaven, brought forth bitter and poisonous Fruit; as in the two Verses next preceeding the Text.”

Edwards asserts that the meaning is that such people are always exposed to destruction, indeed, to sudden, unexpected destruction, and are liable to fall of themselves. And in due time it will happen. The only reason it hasn’t already occurred is that it isn’t yet God’s time for this. Only God’s mere pleasure keeps such persons out of hell. No one can restrain God’s mighty hand. Further, such persons deserve to be cast into hell. Justice dictates this. They are already under sentence; it’s just a matter of time. John 3:18, “He that believeth not is condemned.”

They are now the Objects of that very same Anger & Wrath of God that is expressed in the Torments of Hell: and the Reason why they don’t go down to Hell at each Moment, is not because God, in whose Power they are, is not then very angry with them; as angry as he is with many of those miserable Creatures that he is now tormenting in Hell, and do there feel and bear the fierceness of his Wrath. Yea God is a great deal more angry with Great Numbers that are now on Earth, yea doubtless with many that are now in this Congregation, that it may be are at Ease and Quiet, than he is with many of those that are now in the Flames of Hell.

Edwards adds:

God has so many different unsearchable Ways of taking wicked Men out of the World and sending ‘em to Hell, that there is nothing to make it appear that God had need to be at the Expence of a Miracle, or go out of the ordinary Course of his Providence, to destroy any wicked Man, at any Moment . . . So that thus it is, that natural Men are held in the Hand of God over the Pit of Hell; they have deserved the fiery Pit, and are already sentenced to it; and God is dreadfully provoked, his Anger is as great towards them as to those that are actually suffering the Executions of the fierceness of his Wrath in Hell, and they have done nothing in the least to appease or abate that Anger, neither is God in the least bound by any Promise to hold 'em up one moment; the Devil is waiting for them, Hell is gaping for them, the Flames gather and flash about them, and would fain lay hold on them, and swallow them up; the Fire pent up in their own Hearts is struggling to break out; and they have no Interest in any Mediator, there are no Means within Reach that can be any Security to them. In short, they have no Refuge, nothing to take hold of, all that preserves them every Moment is the meer arbitrary Will, and unconvenanted, unobliged Forbearance of an incensed God.

Edwards begins his application or use: “The Use may be of Awakening to unconverted Persons in this Congregation. This that you have heard is the Case of every one of you that are out of Christ.” Only air is between you and hell, and only God in his pleasure keeps you out.

Your Wickedness makes you as it were heavy as Lead, and to tend downwards with great Weight and Pressure towards Hell; and if God should let you go, you would immediately sink and swiftly descend & plunge into the bottomless Gulf, and your healthy Constitution, and your own Care and Prudence, and best Contrivance, and all your Righteousness, would have no more Influence to uphold you and keep you out of Hell, than a Spider’s Web would have to stop a falling Rock . . .

The God that holds you over the Pit of Hell, much as one holds a Spider, or some loathsome Insect, over the Fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; his Wrath towards you burns like Fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the Fire; he is of purer Eyes than to bear to have you in his Sight; you are ten thousand Times so abominable in his Eyes as the most hateful venomous Serpent is in ours. You have offended him infinitely more than ever a stubborn Rebel did his Prince: and yet ‘tis nothing but his Hand that holds you from falling into the Fire every Moment: ’Tis to be ascribed to nothing else, that you did not go to Hell the last Night; that you was suffer’d to awake again in this World, after you closed your Eyes to sleep: and there is no other Reason to be given why you have not dropped into Hell since you arose in the Morning, but that God’s Hand has held you up: There is no other reason to be given why you han’t gone to Hell since you have sat here in the House of God, provoking his pure Eyes by your sinful wicked Manner of attending his solemn Worship: Yea, there is nothing else that is to be given as a Reason why you don’t this very Moment drop down into Hell . . .

You hang by a slender Thread, with the Flames of divine Wrath flashing about it, and ready every Moment to singe it, and burn it asunder; and you have no Interest in any Mediator, and nothing to lay hold of to save yourself, nothing to keep off the Flames of Wrath, nothing of your own, nothing that you ever have done, nothing that you can do, to induce God to spare you one Moment.

He then spoke of whose wrath this is, how fierce it is, how God aims to show the whole universe that this is his just and terrible vengeance, akin to when Nebuchadnezzar heated the furnace seven times hotter, and how everlasting this wrath is. Edwards also pointedly made his application to those in his congregation who had not claimed conversion:

Consider this, you that are here present, that yet remain in an unregenerate State . . . Thus it will be with you that are in an unconverted State, if you continue in it; the infinite Might, and Majesty and Terribleness of the Omnipotent GOD shall be magnified upon you, in the ineffable Strength of your Torments: You shall be tormented in the Presence of the holy Angels, and in the Presence of the Lamb; and when you shall be in this State of Suffering, the glorious Inhabitants of Heaven shall go forth and look on the awful Spectacle, that they may see what the Wrath and Fierceness of the Almighty is, and when they have seen it, they will fall down and adore that great Power and Majesty.

Because there were many in Edwards' congregation that had not professed their faith, he warned them, “There is Reason to think, that there are many in this Congregation now hearing this Discourse, that will actually be the Subjects of this very Misery to all Eternity.” Finally, at the end, he comes to the benefit of his preaching: “And now you have an extraordinary Opportunity, a Day wherein Christ has flung the Door of Mercy wide open.” Edwards was preaching this in the midst of the Great Awakening, and therefore he added, “God seems now to be hastily gathering in his Elect in all Parts of the Land; and probably the bigger Part of adult Persons that ever shall be saved, will be brought in now in a little Time.” In his second-to-last paragraph he spoke of the axe being laid at the root of the trees, as in the days of John the Baptist. He then finished, “Therefore let every one that is out of Christ, now awake and fly from the Wrath to come. The Wrath of almighty GOD is now undoubtedly hanging over great Part of this Congregation: Let every one fly out of Sodom: Haste and escape for your Lives, look not behind you, escape to the Mountain, least you be consumed.”

Could you say amen to this sermon?

I’m certain that you are beginning to understand some key points of the context of the Great Awakening. It came in the context of a few generations after the initial colonization and settlement. The next generations were not sharing their parents’ zeal, religious affections, and commitments. People sensed that something was lacking. They were awakened to renew their relationships with God, to try to find back what the earlier settlers appeared to have had. Their leaders wanted to preserve a Christian society. Edwards’s sermon, from 1741, was extremely forceful as an effort to restore his church and his town to covenant faithfulness, to a truly felt love for God.

Jonathan Edwards, the half-way covenant, the Lord’s Supper.

Edwards was now 46 years old and had served the Northampton church about 23 years. He knew that his views on admission to the Lord’s Supper had changed and that the church would have a hard time accepting this change. At the same time he knew that in good conscience before God, to give glory to God and his Word, he could not continue with the existing practice in good conscience. Edwards wrote that to embrace in “the highest acts of Christian society” those who “manifest no evidence of saving faith or of sanctifying grace” is to bring “enemies of the cross of Christ” into communion. In question was a person’s church membership, voting privileges, communion at the Lord’s Table, and presenting one’s children for baptism. For Edwards this was about distinguishing the church from the world—only those who profess to be in Christ, as true Christians, should be permitted these blessings.

Indeed, the Lord’s Supper is the height of communion with God, the seal of the love fellowship of the Father with us through his Son, mediated by his Spirit. We have become the righteousness of God and our Father even delights in us. He seats us at his table to say that we are in his family. We sin if we seal this promise and communion to those who have not publicly confessed Christ, who do not seek to worship him with all their heart, soul, and strength.

Edwards was afraid that in Northampton in 1749 there might be tumult, and that on the Lord’s Day, if a minister were to withhold the Lord’s Supper from any adult who came for it. They were “Christian citizens.” Therefore Edwards chose not to preach freely about it, but to ask permission. A Council of ministers from his county refused his request. The whole affair was drawn out over months. Since he could not preach about it, he asked the church to let him complete a book on the topic and then he would resign if they would not agree with him. One of the conditions was that they had to read it.

The book was done in August 1749. Did the people of Northampton read it? They did not. Only twenty copies were sold in his town.

In October 1750 Edwards’ opponents brought to the town meeting (i.e., the Precinct meeting) the question about whether Edwards should continue as the minister of the church. The Precinct clearly said that if his views did not change, he should be separated from his church. Unrest continued. Murray states that the Precinct had more influence in the process than a church committee. A tangled mess of meetings occurred, without much clarity or progress.

As it was clear to Edwards that his people were not considering his biblical arguments, he asked permission to lecture on the topic on Thursday evenings. He did this for five weeks in Feb-Mar 1750. Very few of his own members attended, whereas a significant number of outside persons did. It seems that the outsiders wanted to become informed to equip themselves to oppose his plan for stricter practices. No doubt there were many who spoke against his new views and his plans. Chief among them was a younger cousin of his.

Once when he was out of town his church met twice to try to decide what to do without him running the meeting or trying to persuade them differently. On the Sunday after his lectures were done, he called a meeting for the next day—Monday, March 26. Ninety percent of his congregation voted against keeping him if he would maintain his new views on restricting membership. This might have ended his ministry, but both parties agreed to seek the opinion of a “council,” made up of some ministers. This council had a role to play at various junctures in the year-long process. The minister and the church members had debated and voted a number of times as regards which ministers would be on the committee.

Whereas his church had voted 90% to dismiss him, a council of ministerial colleagues that the church and he had agreed to engage, voted 10-9 to dismiss him. It was close, but the decision had been taken. Edwards preached his farewell sermon July 1, 1750, on 2 Cor 1:14, “just as you have partially understood us— that we are your reason for pride, just as you also are ours in the day of our Lord Jesus.” He showed more care for their eternal well-being than for his own loss of calling. A member of that council, sympathetic to Edwards, stated in his diary that Edwards did not flinch or show the least displeasure.

Presbyterian?

Given the outcome of this year-long debate, given the long process of tussle and disorder, and given the lack of elders among the Congregationalists, it’s not surprising to find that Edwards had a high view of Presbyterianism. His grandfather Stoddard had written in 1700 about the independency being “too ambitious a thing for every small congregation.” He wanted some ministerial cooperation such as the Presbyterians practiced. Edwards had interned in New York in a Presbyterian church. He wrote to John Erskine of Scotland, “I have long been perfectly out of conceit [=lacking pride] of our unsettled, independent, confused way of church government in this land; and the presbyterian way has ever appeared to me most agreeable to the word of God, and the reason and nature of things.”

We should not think that a presbyterial system, with ruling elders, would have kept Edwards in Northampton. Every system can be abused. But it is good to follow the directions of Christ and his apostles for governing the church with a body of elders, a presbytery. Moreover, it is good to have a smaller dedicated group of men who are responsible to study doctrine more closely and who have to work closely with the pastor and will understand his motives and positions better than a whole church that refuses to read what he writes. Let us thank God for our consistories, for our understanding of what it means to have authority given by Christ, and for men who do take this office and calling seriously. Let us equip ourselves to help and bless them in this task.

Religious Affections

The main thing to keep in mind is that Edwards was trying to ascertain from Scripture and from experience which religious affections truly indicate an awakening that is real. Where is the Holy Spirit doing the work of true regeneration? He looked for the persistence of having a lively faith, of doing good, of fighting temptation, of embracing humility. The real would be known by its perdurance. Progress would depend on the mind being enlightened—the affections and the thinking must be united. The converted must learn new things. Racing emotions are not the thing to rejoice in, but settled religious affections that embrace faith, hope, and love, that seek the glory of God and the good of others. He concluded that Christian practice or holy life is the chief of all signs of grace both as evidence to others (XIII) and evidence to oneself (XIV). This is superior to having people describe their daring emotional experiences.

Jonathan Edwards saw affections as “strong inclinations of the soul that are manifested in thinking, feeling and acting.” Many people today are inclined to identify the “affections” as “emotions.” The affections, however, are deeper and longer lasting. They can be called passions, desires, felt intentions, determinations. We include them in the Canons of Dort III/IV, art. 1. The following chart, from McDermott, summarizes the differences between affections and emotions.

| Affections | Emotions |

|---|---|

| Long-lasting | Fleeting |

| Deep | Superficial |

| Consistent with beliefs | Sometimes overpowering |

| Always result in action | Often fail to produce action |

| Involve mind, will, feelings | Feelings (often) disconnected from the mind and will |

| As we noted, Edwards ministered in an era when introspection increased. Yet I think he himself truly rejoiced in Christ, not in the emotional experience. He deeply and truly sought to give glory to God. He was determined not to waste a moment of his time, but to give his life entirely into the service of God. He also lived in the era when the commitments and determinations of the earliest settlers were falling away. The following generations were not fleeing persecution. They were not building the ground-up structures of society. They were no longer religiously homogenous. In that context, Edwards prayed, preached, and wrote for revival, for awakening. |

The Great Awakening and the role of George Whitefield, a contemporary of Edwards.

In sum, the Great Awakening was a series of periods of spiritual revival in New England churches in the 1730s and 1740s, especially years 1742–1745. It was driven by intensely personal preaching, devoid of sacraments or other ceremonies. Membership in the churches increased, church attendance increased, Bible studies became more serious, prayer life improved, and care for the social problems in society also improved. Much started with preaching for the unconverted in the church, but there were also many who attended the great preaching events who were not churched and who became convicted.

It used to be called the First in contrast to the Second, a more populist, simpler, emotional, and Arminian series of Awakenings. Historians have shifted their language to speak of the “Great Awakening” under Edwards, Whitefield, and Wesley, and to speak of ongoing revivals and awakenings thereafter, but not so much a second period that can be delimited and defined.

We must set this Great Awakening in the background of the Enlightenment and the Congregational Churches of New England. The Enlightenment especially affected the upper classes with Deism, whereby they were taught that God had no care for their daily lives, nor did they strive for a living and experienced relationship with him. We already learned about the laxity in the Congregational churches, as we studied Edwards.

George Whitefield (1714–1770)

Born in and died in the Church of England. Although he followed some rather unorthodox methods of preaching and worked outside of the normal church structures, he had a huge impact on culture in the colonies.

- Was to be an actor

- Became a preacher, itinerant

- Raising money for orphanages

- See Diary of Benjamin Franklin

- Me-so-po-ta-mi-a. Swoon!

- Major attraction

- See Diary of Nathan Cole

- 15000 preaching occasions

- 30,000 people could hear at once – see the diary of Benjamin Franklin

- Reformed soteriology

- Weak ecclesiology

- Whitefield's approach to church structure and governance was less formal and more focused on the message of salvation rather than the institutional aspects of the church. This led to some criticism from those who believed in a more structured church polity.

- Democratic, populist impulses

- Whitefield's preaching style and message resonated with the common people, and his emphasis on personal conversion and salvation appealed to a broad audience. This populist approach helped to democratize religion in the colonies, making it more accessible to the masses.

Let’s read the Diary of a farmer named Nathan Cole. It will help us understand what it was like to get on your horse and ride hard in order not to miss Whitefield’s preaching. We will also get a sense of how Whitefield was not afraid to preach personally about total depravity, sovereign grace, and divine election.

- Whitefield's preaching style and message resonated with the common people, and his emphasis on personal conversion and salvation appealed to a broad audience. This populist approach helped to democratize religion in the colonies, making it more accessible to the masses.

- Is it okay to preach to people and tell them they need to be justified, yet not care about what church they join? Or whether they join at all?

- Whitefield's focus was on the message of salvation, but some critics argued that he neglected the importance of church membership and accountability.

- Isn’t our calling to a total obedience to Christ?

- Whitefield’s emphasis on personal conversion and salvation was a call to total obedience, but it also raised questions about the role of the church in guiding and discipling believers.

- Don’t we need to be in a place where we are accountable and will contribute our gifts?

- While Whitefield’s preaching was powerful, it sometimes lacked the follow-up needed to ensure that converts were integrated into a church community where they could grow and serve.

- Doesn’t Scripture have much to say about the church as the body of Christ, in very practical terms?

- Whitefield’s ministry highlighted the need for personal salvation, but it also underscored the importance of the church as the body of Christ, where believers are called to live out their faith in community.

- Finally, isn’t the real life lived out in the daily grind, when Nathan Cole is plowing his field and milking his cows and fixing his barn? Yes, revival. But regular faithful service is better.

- While revival moments are important, the Christian life is ultimately lived out in the day-to-day faithfulness of ordinary life. Whitefield’s preaching inspired many, but the true test of faith is in the consistent, faithful living of believers in their daily lives.

John Wesley (1703–1791)

John Wesley was born and died in England, in the Church of England. Although he remained an Anglican throughout his life, he is best known as the founder of Methodism.

-

Anglican but founder of Methodism. 40,000 sermons.

- Wesley was a prolific preacher, delivering an estimated 40,000 sermons in his lifetime. His preaching was instrumental in the spread of Methodism.

-

Moravian influences. Small groups. Organizer.

- Wesley was influenced by the Moravians, particularly their emphasis on small group meetings for spiritual growth and accountability. He organized similar groups within Methodism, known as "class meetings."

-

Works outside regular channels. Orphanages, etc.

- Like Whitefield, Wesley worked outside the traditional structures of the Church of England, establishing orphanages and other charitable works.

-

New birth

- Wesley emphasized the necessity of a "new birth" or conversion experience, where individuals are born again through faith in Christ.

-

Holiness

- Wesley taught that Christians should strive for holiness, or sanctification, in their daily lives. This was a central theme in his preaching and writing.

-

Perfection. Possible to end all scheming to sin

- Wesley believed in the possibility of Christian perfection, where believers could reach a state of love and holiness that would free them from intentional sin. However, he acknowledged that he himself had not yet attained this state.

-

“The Arminian” magazine 1778

- Wesley was a staunch Arminian, rejecting the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. He published "The Arminian" magazine to promote his theological views.

-

Public dispute with Whitefield re. Calvinism

- Wesley and Whitefield had a public theological dispute over Calvinism, particularly the doctrines of predestination and election. Wesley argued for a more general atonement and the freedom of human choice.

-

General atonement

- Wesley believed that Christ’s atonement was available to all people, not just the elect.

-

Prevenient grace for all people

- Wesley taught that God’s prevenient grace (the grace that precedes human decision) is given to all people, enabling them to respond to the gospel.

-

Freedom of choice

- Wesley emphasized human free will, arguing that individuals have the ability to choose or reject God’s offer of salvation.

-

Methodist circuit preachers

- Wesley organized a system of circuit preachers who traveled from town to town, spreading the Methodist message and establishing new congregations.

-

Fire-and-brimstone sermons

- Like Edwards and Whitefield, Wesley’s preaching often included strong warnings about the consequences of sin and the need for repentance.

-

Already in the 1780s Methodist churches were organizing under the umbrella of the Church of England

- Although Wesley remained within the Church of England, Methodist societies began to organize themselves more formally in the 1780s.

-

Wesley would not condone schism, but in 1791, after his death, his followers split from the Church of England

- Wesley was reluctant to break away from the Church of England, but after his death in 1791, the Methodist movement formally separated and became its own denomination.

Conclusion

The Great Awakening, led by figures like Jonathan Edwards, George Whitefield, and John Wesley, was a transformative period in American religious history. It emphasized personal conversion, the need for revival, and the importance of a living, experiential faith. While each of these leaders had different theological emphases and methods, they all contributed to a renewed focus on the individual’s relationship with God and the need for holiness in daily life.

Edwards’ deep theological reflections, Whitefield’s powerful preaching, and Wesley’s organizational genius all played crucial roles in shaping the religious landscape of the American colonies. Their legacies continue to influence Christian thought and practice today, reminding us of the importance of a vibrant, personal faith and the need for continual revival in the church.

Week 4: Democratization and Revivalism (19th c. American Christianity)

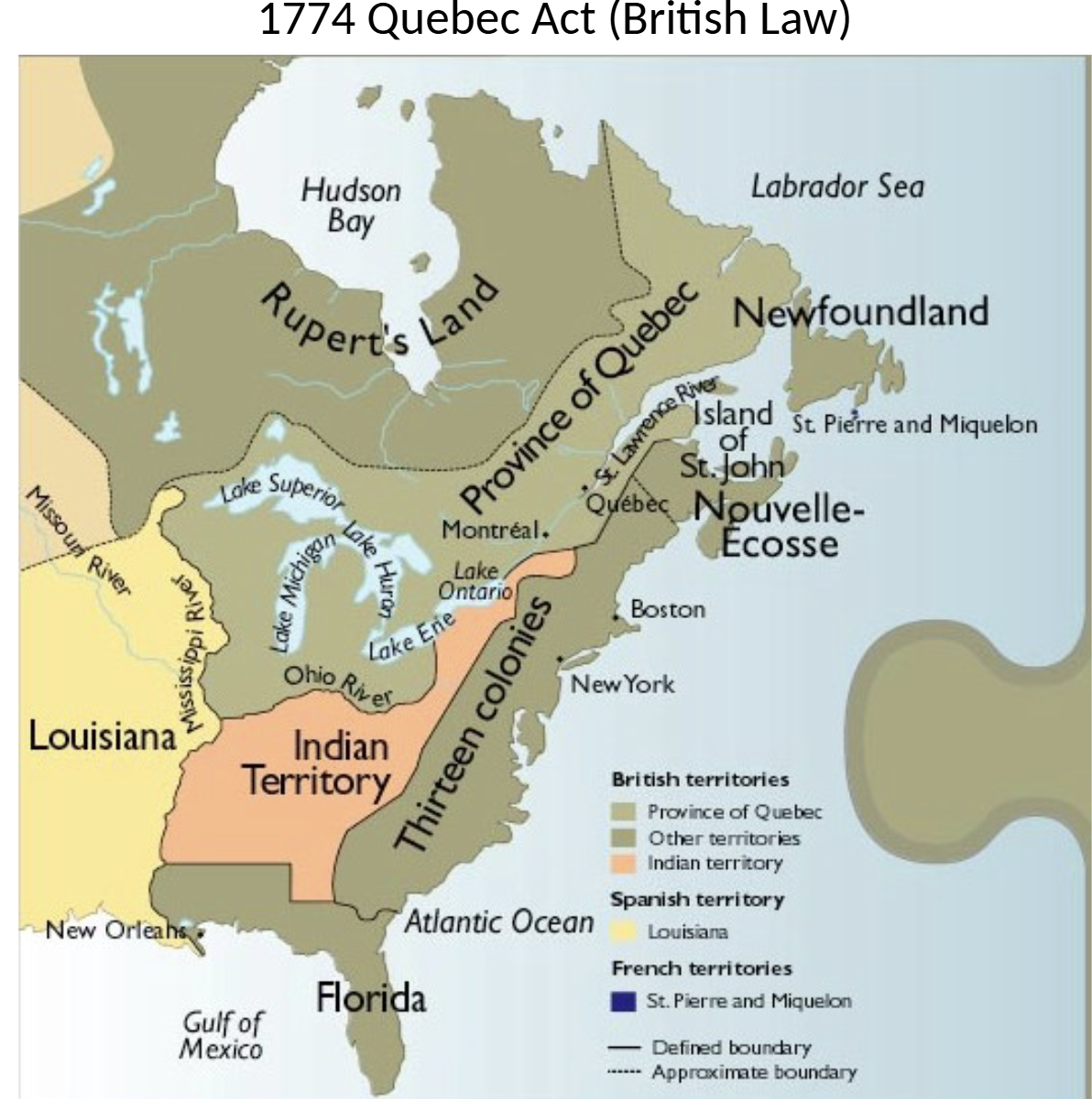

- 1774 Quebec Act: British Law

- Louisiana: French territories

- British Territories: Province of Quebec, Indian territory, Spanish territory

- Defined and Approximate Boundaries

Declaration of Independence (1776) and Expansion of the United States (1783) - British North America

- U.S. Territory: Gained by Treaty of Paris (1783)

- Original 13 States: Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, etc.

- Spanish Territory: Florida, Louisiana

America in the 18th Century

- Revolution in 13 Colonies (1776 Declaration), not in Canada

- Growing Pluralism: Established churches like Church of England & Congregational

- I.E to hold political office one needed to be a church member.

- Awakening/Revival: Edwards, Whitefield, Frelinghuysen

- Reformed Doctrinal Origins: Anglican, Congregational, Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist

- Growth on the Frontier: Itinerant preachers, cell groups, end of established churches

Awakenings

- First Great Awakening (1742-1745): Whitefield, Wesleys, Tennents

- Declaration of Independence (1776)

- Treaty of Paris (1783)

- First Amendment (1791): No established church for the union

- More Awakening(s) (1790-1820):

- An ongoing desire for revival. Arminian influences, new denominations, camp meetings, emotionalism. Becomes common

Why the Many Moments of "Awakening"?

- Pietiestis of Germany, Puritans of England, The Nodere Ref. of the NL

- Pan-European and American Revival of Piety

- Established Churches Growing Cold

- Moral decay, spiritual lethargy

- Presbyterian "Seasons of Communion"

- Moravian Piety and Social Activism

- Established Churches Growing Cold

- Frontierism and Expansionism

- Aversion to Professionalism and Class Structures

- Impersonal deism

- Reign of Terror 1789 in France as a warning

- Desire for Mystery Amid Progress

- Even today many in Silicon Valley have fascination with Buddhism.

- Individualism and Voluntary Emphasis

Nathan Hatch on 19th Century America

- The Democratization of American Christianity (1989)

- Examined Five Movements:

- The Christian Movement: all other Churches are in error.

- The Methodists

- The Baptists

- The Black Churches

- The Mormons: Non trinitarian

- Could Have Added: Seventh-Day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Christadelphians

Central Argument of Hatch

- Leaders Without Formal Training (Barton Stone, William Miller, Francis Asbury, John Leland, Richard Allen, Joseph Smith) went outside normal denominational frameworks to develop large followings by the democratic art of persuasion. These are unbranded individualists who stormed heaven by the back door (Hatch, 13)

Democratization & Egalitarianism at Work

- Relentlessly Energetic Young Men: Passion for expansionism

- Hostility to Orthodox Belief & Style: Ready to reconstruct all

- They offered people, esp. the poor visions of self-confidence.

- Self-Respect and Self-Confidence for the Poor: Interpret Scripture yourself

- Church Re-Made in the Common Man’s Image:

- Commoners as leaders

- Simple doctrine

- Lively and singable music

- Ordinary people’s religious experiences taken at face value

- No oppressive authority structures

- Wide use of mass media: pamphlets, tracts, broadsheets, newspapers

Hatch: An Irony

- Rise of Popular Sovereignty: Insurgent leaders glorifying the many to legitimate their own authority.

- Democratization of Christianity: Less about polity and governance, more about incarnation into popular culture.

- You don't have so much a reveloution, but they don't throw off religion; they put it on the way that shapes with independence and freedom.

- Institutionalization: Charisma only goes so far

Revivalism and Anti-Professionalization

- Lawyers, Doctors, Ministers: These are professional duties, in the midst of the enlightenment these are highly trained men.

- Doctors are quacks, lawyers are frauds and cheats, ministers are charlatans.

- Religion of the people, by the people, for the people.

- "Who knows their own body better? The individual!"

Restorationist Movement

- "Who knows their own body better? The individual!"

- No Creed but Christ, No Book but the Bible, No Name but Christian

- Barton Stone, Alexander Campbell, Elias Smith

- Stone did not even want his reading of the Bible from a week ago to influence his reading from the present day.

- Restoration of the Original Church of the New Testament

- Throwing off the names of denominations, protestants, throws off name presbyterian by their 'declaration of independence'

Charles Finney (1792-1875)

- Converted at 29: Promised God he'd be a pastor. Did not want to go to seminary.

- Trained Presbyterian, Irregularly.

- Seminaries were not preparing the ministers well to interact with the common people.

- Called at 31, claimed to not have studied the WC but is called anyway

- 32 becomes an itinerant preacher

- New Measures: Personal prayer, late meetings, anxious bench (if you felt anxious about hell, salvation you would sit at the front bench), extended stay, allowed female preachers

Finney's Teachings

- Human Constitution Not Morally Depraved

- Imputation of Adam's Sin a Fiction

- Spiritual Inability Not Correct

- Universal Atonement: Without obligating God to save anyone

- Social Reformer, Moralist (this is how he gets his hearers)

- Revival Not a Miracle: Follows "method"

The Method of Finney’s Revivals- Scientific Enterprise: Predictable according to spiritual laws

- Lectures on the Revivals of Religion (1846): Revival is not a miracle but a result of the right use of means

John Williamson Nevin (1803-1886)

- German Reformed: "Mercersburg Theology"

- Union with Christ, real presence of Christ in the LS

- The Anxious Bench (1843):

- A clear critique of Finny and revival "Science"

- A method is no proof of truth, no method to revivals.

- Outward method as key is a Romish error

- It is quackery

Charles Hodge (1797-1878)

- Constitutional History of Presbyterian Church in USA

- Reviews the Great Awakening: Edwards, Tennent, etc.

- Reviews Further Awakenings: Are the doctrines biblical? Are the experiences spiritual? Are the effects godly in the long term?

Were Reformed Anti-Revivalists Rationalists?

- YES, said...:

- Historians: Perry Miller, William Livingstone, Sydney Ahlstrom, George Marsden, Mark Noll

- Historians of Theology: Jack Rogers, Ernst Sandeen, Donald McKim, Theodore D. Bozeman

- NO, replied...:

- Andrew Hoffecker, John Woodbridge, Paul Helm, Richard Muller, David Calhoun, Paul Helseth

Paul Kjoss Helseth, “Right Reason” and the Princeton Mind

- An Unorthodox Proposal (2010)

- Primary Source Evidence: Alexander and Hodge and Warfield

Week 5: Gresham Machen vs Liberalism

[[Machen History and Faith 1915 (marked up).pdf]]

J. Gresham Machen (1881–1937)

- From Baltimore, MD

- Top honours student

- Family close to Woodrow Wilson (US President)

- Highlights of work:

- Published his own Greek for his beginners.

- Spoke and read classical Greek to relax.

- Princeton University and Seminary at the same time philosophy graduate degree.

- Study year in Germany: wanted to be familiar with all sides, interaction with critics.

- Intellectual honesty

- Returned to US to teach in Princeton.

- Funny antics: while lecturing he would slowly bend forward until his head hit the wall, and then he would just stay there.

- Never married; lived with students he taught.

- 1929 Founded WTS

Subsequent investigation and meditation have shown me, as over against such youthful folly, that Warfield was entirely right; I have come to see with greater and greater clearness that consistent Christianity is the easiest Christianity to defend, and that consistent Christianity—the only thoroughly Biblical Christianity—is found in the Reformed faith.

- Book: Christianity and Liberalism

- Liberalism places emphasis on man, while Christianity places emphasis on God and his word.

- Liberals: Split faith and reason, making faith only a personal experience.

- Machen: This is anti-intellectual. Places faith into a realm that could not be critiqued.

- "And" in a sense means "verses"

- Liberalism places emphasis on man, while Christianity places emphasis on God and his word.

Fundamentalist—Modernist Controversy

- The Fundamentals at Presbyterian General Assembly in 1910

- Five affirmed points:

- Scripture inspired by the Holy Spirit and thus inerrant

- Virgin birth

- Christ truly made atonement

- Christ rose bodily

- Christ’s miracles truly occurred as historical events

The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth (1910–1915)

- Five affirmed points:

- Intended to stop the spread of Christian Liberalism, wealthy laymen funded the work of multi-volume theologies. The aim was to lay out the basics of the Christian faith, while also defending and critiquing liberal ideas.

- Authors were Presby, Baptist, Anglican

- Previous essays from J.C Ryle included

- Authors were Presby, Baptist, Anglican

- Not everyone was against Darwin outright. The authors were intellectuals, not idiots.

- Response to higher criticism

- "Shall the Fundamentalists Win?" (1922)

- Two views on Virgin birth?

- Two views on inspiration

- Two views on Christ's return

- Thus: we should have tolerance.

- "Shall the Fundamentalists Win?" (1922)

- Widely distributed (64 authors, 90 essays)

The Auburn Affirmation (1924)

- A modernist confession:

- God is immanent in nature

- The Holy Spirit is the God of love experienced in human life

- Humanity without God cannot have a full moral life

- Forgiveness transforms human life

Auburn Affirmation

- Rejected inerrancy of the Bible

- General Assembly (GA) cannot dictate doctrine

- GA acted contrary to BCO

- 5 Fundamentals (see above) not necessary

- Liberty of thought is good; division over doctrine is bad

Digression: Scopes Monkey Trial

- William J. Bryan, a three-time presidential candidate and Presbyterian. He opposed Darwinism and linked it to German militarism. Bryan advocated for banning the teaching of evolution in school.

- A Highschool teacher in Tennessee, Scopes, disobeyed and taught it anyway. He went through a trial which attracted international media attention. He was found guilty, yet, the 'fundamentalists' were smeared and discredited.

Trial: - January 1925, before the trial, Bryan emphasized that this was a theory, not a fact.

- Machen asked to be an expert witness, declines.

- Bryan acts as counsel for State of Tennessee. In private, he believed in evolution for plants, animals, but not for man. He thought it could be taught as a theory, but not as a fact. Yet, had to defend a stronger law, which ended up damaging his image.

- Did not hold to a literal day theory which hurt his reputation among supporters.

- Bryan died 5 days after the trial.

- Law stayed in place until 1967

Battle for Princeton

- Princeton battle between conservatives and modernists.

- Machen argues that liberals follow a different religion and can't live in one church.

- Moderates want tolerance.

- GA set up a committee to investigate division at PTS. Committee recommended a "reorganization" allowing liberals control.

- Machen, Oswald Allis, Cornelius Van Til, and Robert Dick Wilson left Princeton (Vos stayed)

- Westminster Theological Seminary (WTS) founded in 1929 with Machen’s funds

- 1930 John Murray joins.

- Machen chose a diverse background of Reformed faculty (Dutch, Scottish, English)

The (Independent) Board of Foreign Missions and the Start of the OPC

- Machen remained in Presbyterian Church but opposed pluralistic missions

- Writes 100 page against pluralistic missions, disregarded.

- Established an independent Board of Foreign Missions.

- Church trials (1934–1935)

- Defrocked at GA 1935 for refusal to do independent Board of Foreign Mission

- Appeal to GA 1936 rejected - 2million members at the time

- Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) founded in 1936 - 5000 members

- Machen died on January 1, 1937

- Last known words, "So glad for the active obedience of Christ, no hope without it."

- J.I Packer, "Jesus Christ constituted Christianity a religion on biblical authority. He is the Church’s Lord and Teacher; and He teaches His people by His Spirit through His written Word."

Week 6: Billy Graham (1918-2018)

- Born in North Carolina, raised Presbyterian (ARP)

- Became Southern Baptist 1953

- mostly reformed minded

- Youth For Christ employee

- Crusade in 1949 in Los Angeles

- Three weeks of meetings and preaching, led to media attention, led to 9 weeks of preaching.

- Itinerant Preaching

- Radio program: The Hour of Decision

- Too large an emphasis on decision process?

- Gospel felt very clear, call to conversion

- Founded Christianity Today

- Highly inclusive

- Involvement of local churches

- Preached in Hamilton (1988) with support from 470 (including 60 RCC) local churches

- Three pressures to collaborate (or compromise): Father in law had a personal influence, wealthy patron, mainstream church leaders want to come and help.

- Less likely to reach liberals if he does not include them.

- Racial inclusion: all races from many nations were apart of the crusades.

Billy Graham message in Hamilton:

- Involvement of local churches

- Strong voice, strong urgency of accepting the gospel.

Billy Graham (1918-2018) – Legacy - Preached in 185 countries to 210 million people

- Direct personal influence on 12 US presidents

- Body lay in honor in the US Capitol Rotunda

- Multiple awards (academic, social, political, musical)

Caution from Iain Murray: - Collaboration can lead to compromise

The Jesus Generation by Graham

- Published in 1971, Focused on "The Jesus People" movement

- Counter-Hippie Movement

- Using the language of hippies

- Yet giving the gospel content

- Maintaining gospel truth

Week 7: Pentecostalism

Beginning: The Apostolic Faith Mission on Azusa Street, now considered to be the birthplace of Pentecostalism.

- Charles Fox Parham (1873–1929)

- baptism of the Holy Spirit and fire, (after becoming Christian), speaking with other tongues. Emphasis on other gifts of the spirit, including healing.

- William J. Seymour (1870–1922)

- Speaking in tongues

- Azusa Street Revival 1906

- Woman inclusion

- Restorationist mindset

- return of Christ expected, a need to encourage the return through the restoration of the Church to its apostolic roots.

Earlier awakenings...Responses to 18th c. Awakening

- return of Christ expected, a need to encourage the return through the restoration of the Church to its apostolic roots.

- Jonathan Edwards, c. 1740

- Religious affections: New England. Best evidence is the long pursuit of a holy life.

- George Whitefield

Responses to 19th c. Awakenings - John Williamson Nevin (Anxious Bench)

- Charles Hodge

That the fanatics, who regarded these bodily agitations and cries as evidences of conversion, committed a great and rigorous mistake, need not be argued; and that Edwards and Iers, who rejoiced over an encouraged them, as probably tens of the favour of God, fell into an error scarcely less irious to religion, will, at the present day, hardly be questioned at such effects frequently attend religious excitements is no of that they proceed from a good source. They may owe their sin to the corrupt, or at least merely natural feelings, which lays mingle, to a greater or less degree, with strong religious ercises . . . [they] are quite as frequently experienced by those so know nothing of true religion . . . they have prevailed, in some of general excitement, in all ages and in all parts of the old, among pagans, papists, and every sect of fanatics which is ever disgraced the Christian church . . . they arise under the circumstances, are propagated by the same means, and bodily agitations attending the revival, were in like manner pagated by infection. On their first appearance in Northampton, a few sons were seized at an evening meeting, and while others looked on, by soon became similarly effected; even those who appeared to have no merely out of curiosity did not escape . . .scription of the “Jerking Exercise” etc. development of innovative new religious practices known collectively he “bodily exercises.” Men and women in the throes of conversion apsed to the ground, then rose up and began dancing. Others lay ensate for hours, enraptured with dramatic visions of heaven and help meeting participants barked liked dogs, scampered up trees, aged in trance walking, ran headlong through the woods, faced off in ck boxing matches, and burst into uncontrolled peals of holy laughter. Servers witnessed people speaking in unknown tongues and claimed e heard music issuing miraculously from the chests of young yerts . . . none drew more astonished commentary or more virulent position than “the jerks”: involuntary convulsions in which the subject

Further Manifestations

- Glossolalia - gibberish speaking

- Stories of this being real languages, does not seem to be demonstrated

- People often uses English, phonetic sounds, then randomly repeat them.

- Women in office

- Phoebe Palmer 1857 Hamilton revival

- Publication: Asa Mahan, Baptism of the HS. This work opened the door to speaking in tongues.

- Aimee Semple McPherson

- The foursquare movement: 8.8 mill

- Phoebe Palmer 1857 Hamilton revival

- The faith-healer movement

- Oral Roberts (1918–2009)

- faith healer, media savvy, needed to fundraise 8million or God would 'take him out of the world' when it succeeded he said his healing powers were renewed and

- Kathryn Kuhlman (1907–1976)

- Never quotes a text, denies that she is preaching (true in a way)

- Benny Hinn (b. 1952)

- Oral Roberts (1918–2009)

- The prosperity gospel movement

- Kenneth Copeland

- Benny Hinn

- Joel Osteen

- Paula White

- The "I went to heaven and back" movement

- Roberts Liardon

- Colton Burpo - child who went to heaven and back.

- The prophetic movement

- William Branham (1909–1965)

- Connection to Robert Liardon, "WB is the great prophet"

- Used visions to gain crowds, legendary stage presence. KKK member

- Serpent seed theology

- William Branham (1909–1965)

- As an example, the Toronto Blessing.

Costi Hinn

God used

-

His mother’s tumour

-

His choice of college for study

-

His baseball coach

-

His girlfriend, then fiancée Christyne Problems with the prosperity gospel

-

Distorts biblical gospel

-

Insults God

-

Confuses atonement

-

Demeans Jesus Christ as means to end

-

Abuses vulnerable people

-

Perhaps a way to start helping a Pentecostal is to start with the variety of gifts

-

His plea: Please do not remain silent in the face of this evil!

Walter J. Chantry

- Book: Signs of the Apostles

Outline: - Purpose of miracles

- Completion of Scripture

- Purpose of gifts in the apostolic church

- Veracity of apostolic witness

- Spread of the gospel to all nations

- Judgement on Israel

- Baptism with the Spirit as the gift for those who belong to Christ. The Son and the Spirit are united in the work of salvation.

- The Christian life is about the daily joy in the Lord as we repent from sin and pursue righteousness. This Spirit-wrought work is the wonderful thing today.

- Weakness and sin need chastening, and God uses sickness and suffering for good

Week 8: Canada's Christian History

Resources for Canadian Church History

Periodization

- French era, c. 1603–1763